Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Monday, October 29, 2012

LaserJet Transfer

1. You need nitrile gloves (latex or vinyl gloves work too), and empty container, a brush, CitriSolv Concentrate, and a laserjet printout with high color saturation and high contrast and a surface upon which you will transfer the image (typically paper).

2. Put on the gloves and pour a little bit of the CitriSolv into the empty container. You don't need much for this process; just a little bit.

3. Place the laserjet printout face-down against the surface that will accept the transfer. (In this example the surface is a piece of printmaking paper)

4. With just a little bit of CitriSolv on your brush, rub the back of the laserjet print. You will see the image as the paper becomes transparent. The CitriSolv is soaking through the paper and releasing the laserjet toner from the paper.

5. Be sure that the paper does not move or the image will blur. See how I'm holding the paper down with my fingers and thumb as I pull up a corner to show how much toner transfers with this first step.

6. Holding the laserjet paper firmly in place, burnish it with the back of the brush. The high pressure will make more of the toner transfer to the paper on the bottom. You will be able to see the direction you have burnished, so consider the direction you rub.

7. Continue burnishing all around the image. Using the wide side of the brush handle will transfer large areas. Using the thin side will make thin marks, as if you were drawing with a pencil.

8. Notice how much more toner has transferred with burnishing (compared with step 5). You can see the marks made from the brush handle.

9. Here I am using the pointed end of the handle for some thin lines, drawing (rubbing) along contours or textures that will complement the overall image.

10. The paper has to have enough CitriSolv to be damp, but not so much that you see puddles. CitriSolv does evaporate, so you may have to add a little bit more. The amount left in the brush may be enough, so try that first.

11. Keep working until you have as much of the image transferred as you want. Overlapping lines will create a more solid image which is more faithful to the original (and looks more like a real photography), while separations in the lines will make the image look more like a drawing.

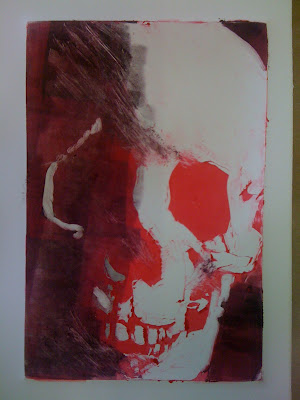

12. Here is the final image compared with the ink that is left on the laserjet sheet. This example is very free, and looks like a pencil drawing.

Let's move on to another example that will show how to make a more faithful photographic image...

13. Here, I have a piece of cotton printmaking paper and a normal laserjet printout without any color adjustments.

14. Tape the laserjet print on to the printmaking paper, face down, so it does not move while working.

15. Spread a thin, even coat of CitriSolv on the back of the print and you will begin to see the image. Let the CitriSolv soak through for a minute, giving it time to release more toner from the original laserjet print.

16. Use a medium-hard brayer (roller) to press across the back of the print, making an even initial transfer from laserjet print to printmaking paper. This requires some real pressure. Push hard. Be sure you are not moving the papers or the image will blur.

17. Roll out perpendicular to the previous direction, applying firm, even pressure across the entire image.

18. If it starts to dry up, add a little more CitriSolv. As in the last example, the amount left over in the brush may be enough.

19. Using the back of the brush, burnish important areas in which you want a faithful transfer. High pressure applied by a brayer will make a good transfer, but burnishing creates higher pressure and will ensure better transfer.

20. Using the tip of the brush, trace lines to transfer areas (if you want some pencil-like lines to transfer in the print).

21. Continue working important areas.

22. The places you choose NOT to transfer can become as important as those that you choose to transfer. Consider the entire composition, and how much information you want to transfer in your final print.

23. Remove the tape from one side and peel back the laserjet print. If you need to transfer more, you can put the laserjet print back down (you DID tape one edge to act like a hinge and make sure that the paper will go back down in the same place, didn't you?).

24. This transfer is a little more faithful to the original photo than the first example. You can see the extra character added with the additional burnishing from the back of the brush.

Sunday, October 28, 2012

Saturday, October 27, 2012

Friday, October 26, 2012

Thursday, October 25, 2012

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Tuesday, October 23, 2012

Monday, October 22, 2012

Sunday, October 21, 2012

Saturday, October 20, 2012

Monotype Printmaking and Collage

Monotype printmaking encourages experimentation through work, and the exploration of a large variety of art-making techniques that can be used to achieve your vision.

Look at the three experiments below.

Use them as guidelines. The goal is to inspire some new ideas.

Choose the ones that will be useful to you,

and continue working with the techniques you have already learned in the first part of this semester.

1. You can collage many things into your print, planning either before or during the process of applying ink to a monotype plate. This example starts with a finished plate; ink applied, it could be run through the press at this stage.

2. But, a last-minute decision to experiment can be fun (although risky).

Tear and cut a piece of paper that is somehow different from the printmaking paper.

The plan for this one is to use white rice paper on top of cream-colored cotton paper.

3. Apply glue to the BACK of the paper you will collage into your print. Elmer's glue-All is a nice predictable product; one that conservators can handle later.

4. Place the paper onto your finished monotype plate, with the glue side facing up.

The glue is going to stick to the printmaking paper, and the other side will receive ink from the plate.

5. Place the monotype plate on the bed of the press.

Put printmaking paper on top.

Put barrier paper on top of printmaking paper to protect blankets.

Run everything through the press.

6. Sometimes experiments are great, sometimes not.

This example worked, but the differences in color (of the two different pieces of paper) was not enough to make any design impact.

You can see the outline of the torn paper, where it slipped on the glue, under the extreme pressure of the etching press.

And, if you were to examine the print in real life, you'd see a slight color shift, but not enough to see in a color-weak internet photo.

On to the next experiment...

7. You can take a more direct collage approach, and use images printed by other means in your monotype. (images printed on inkjet, laserjet, photocopier, etc.)

Keeping those images in mind, ink your monotype plate.

Paint, roll, scratch, and work the plate as much as you want.

8. Cut or tear out the parts you will use in the collage.

Wipe or scrape out some of the ink on your monotype plate, so that the collage elements will show up in the final design.

Allowing for some overlapping ink will make an interesting design, so don't worry about accuracy the first time you do this.

9. Apply glue to the BACK side of the collage pieces.

Make sure to apply thin, even coats.

Any extra will be squeezed out by the high pressure of the printing press and (potentially) ruin your final print.

10. Place the collage pieces on the monotype plate. be sure to place them with the glue side facing UP, and the printed side facing DOWN towards the monotype plate.

11. Run everything through the press like usual.

Monotype plate on the bed of the press.

Printmaking paper on top of the monotype plate.

Barrier paper on top of the printmaking paper.

Blankets on top of everything.

Crank the handle and make a print!!!

12. This one worked a bit better than the last experiment,

but only with respect to how obvious the collage element is in the design.

The same thing can be done with drawings you have made, or with old pieces of art that you have lying around (as long as they are thin enough to fit through the press).

Let's try a third experiment...

13. Make a design on a monotype plate.

This one is a semi-abstracted landscape scene with simple mountains and sky created with a roller (brayer), using all the different colors left over from the last experiment.

14. Draw on a smaller piece of printmaking paper.

This example uses a different color pieces of paper for the drawing thatn what will be used for the main print.

The subtle contrast of paper colors will reinforce the presence of collage.

15. Tear or cut out the design to be collaged into the monotype.

Scissors and razors will give clean lines.

Manual tearing will make rough textural lines.

16. You may choose to leave the drawing alone,

or you may choose to add some color with a brayer (roller) or brush.

Feel free to experiment with both.

17. Hold the collage element over the monotype plate so you can get an idea of where it will be in the final design.

You can estimate (as in this picture),

or take a moment to make some small marks on the inked plate that will show you exactly where the collage element will be placed later.

18. Wipe away the ink where the collage element will be.

This will let it show through.

How much you wipe off depends on how much of the collage element you want to see in the final print.

19. Glue the BACK side of the collage element.

Apply a thin, even layer of glue.

20. Place the collage element on the monotype plate.

Notice the overlap of imperfect wiping in this example.

You may be as accurate or care-free as you like.

Be sure , however, that you are working with intent!

21. Run everything through the press and see the result.

22. This experiment worked.

The sloppy wiping in the blue acts as clouds.

The sloppy wiping in the red/green is a little more difficult to accept.

Keep experimenting, and see what you can make.

You can incorporate just about anything that is on paper:

newspaper/magazine clippings, drawings, pieces of painting on paper (as long as it is thin enough to fit through the press without damaging the equipment).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)